Police in Schools: Laying the Foundation for a Trauma-Informed Assessment of School Resource Officer (SRO) Programs

File: PDF Version Police in Schools: Laying the Foundation for a Trauma-Informed Assessment of School Resource Officer (SRO) Programs

Authors

J. Kevin Cameron, Executive Director NACTATR

Dr. Kevin Godden, Superintendent of Schools, Abbotsford School Division

Contributors:

Dr. Marleen Wong Senior Advisor, NACTATR

Founding Partner, Center for Safe and Resilient Schools and Workplaces

Senior Vice Dean, Suzanne Dworak Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California (USC)

Sandra Montour, Executive Director, Ganohkwasra Family Assault Support Services Ohsweken, Ontario

Patrick G. Rivard Director, Canadian Operations, NACTATR

Introduction

A worldwide pandemic combined with the videos of the recorded deaths of George Floyd and other African Americans in the United States and the death of Chantel Moore during a safety check in Canada, has resulted in a powerful and sustained social movement on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border. Movements demanding changes at the governmental and institutional levels to address systemic racism. A standard in supporting schools and communities impacted by “high-profile trauma” is that “trauma does not generally result in new dynamics in human systems but instead, intensifies already existing dynamics”. This very issue was addressed in initial NACTATR communications during the early phase of the pandemic. It means that if there are unresolved conflicts and issues, especially those borne out of abuse and trauma, the heightened anxiety caused by a new trauma will rekindle and magnify those foundational and systemic symptoms. This includes rekindling whole-race trauma perpetrated hundreds of years ago. In the current context, these are traumas (e.g. colonization, slavery) maintained by systems for so long that many “average citizens”, not oppressed by it, did not even see until now. In the Canadian context, this is evident in the current and historical experience of Indigenous peoples and Black communities as two of the most blatant examples of sometimes overt and sometimes subtle systemic racism

At the center of the current movement to end racism is a multitude of visual recordings and countless more verbal stories originating from the United States to Canada of experiences with police similar to the tragic death of George Floyd. Now in the Canadian context, similar stories are coming to light. This has resulted in some questioning and some demanding that police be removed from schools and that School Resource Officer (SRO) or School Liaison Officer (SLO) programs be terminated. It is this area alone that will be addressed in these initial guidelines as the authors are collectively immersed in this topic as practitioners and leaders. These initial guidelines are being released at this time to take advantage of a natural period for review by decision makers: the summer holidays.

Although many school districts (divisions) and police services have already decided to continue with their SRO program others are considering what position they should take. It is clear that no two schools, two communities or police services are exactly the same and therefore, where concerns have been raised, reasonable data-driven assessments of these programs should occur before making final decisions. Nevertheless, all school-police initiatives should be regularly reviewed and based on evidenced-informed best practice. An ongoing, rigorous and transparent review process allows police and district leaders to more objectively review, with other stakeholders, agreed upon outcomes and not fall prey to the circumstances we now face. Such an ongoing program evaluation regime would allow leaders to assess the extent to which their practices are sufficiently trauma-informed to address the needs of racialized communities.

Uniqueness of Schools

Next to the family, no other system has more influence on children and youth than their school experience. Even peer dynamics and relationships are filtered through these two interacting, adult-led organizations. Evidence of this is the frequency with which many adults reference their school years as providing the most pivotal times in their lives whether positive or negative. As such, the school system has the power to influence students’ perceptions and experiences that will enable them to maintain any gains achieved during this period of social unrest. Schools are also microcosms of society and the school-police relationship is part of that. The fact is, no two schools, communities or police services are exactly the same. An SRO program may work well in a school that was predominately white but as the cultural and racial landscape changes that program may fail to accommodate the cultural dynamic which might perceive the police as traumatic stimuli. In another community the SRO program may have been organized because of “racial tensions” where the specialized police officers in the role were racially representative of the schools they were working in and the programs have flourished. Yet, in another area schools never wanted SROs in their schools and police never wanted them there either but because of political pressure the program was initiated without the commitment necessary to make it thrive. Our experience is that if the right police are in schools that use them properly, there have been many positive outcomes attributable to thoughtful program design and the commitment and service of the SROs. True, there have been occasions when police actions have exacerbated pre-existing tensions in the school. However, our experience is that when the right SROs work in the school environment, they bridge the gap between police being seen by students and parents (caregivers) as the “other” to being seen as human beings with a genuine interest in their child’s whole life experience.

When the SRO Program Works Well

The City of Abbotsford has had a strong and highly regarded SRO program for over two decades, in large part due to a strong commitment from the district and police leadership. The current program is supported by a strong working relationship between the Police Chief and the Superintendent who meet regularly to discuss the program. The squad is comprised of six officers who work closely with the school administration to support the school program in a variety of ways. Officers are selected based on a genuine interest in working with youth and are given latitude in how to engage with each of their schools. This has manifested in an array of interventions which range from classroom presentations co-constructed with teachers to hands-on mentorship of at-risk youth, to direct enforcement. SROs work closely with school administrators, counsellors and youth and family workers and have discretion about how they will become a part of the school community. They engage in joint training with district staff, participate in the social life of the school, and are viewed as an extension of the school family. It is not uncommon the see the SRO being honoured at graduation ceremonies in part because they have “grown up” with the students in their schools. Students and staff in Abbotsford schools will tell you that the single biggest reason for the success of the program is the quality of the SROs and their commitment to building a positive relationship with staff and students.

The Role that Trauma Plays

We underestimate the role that trauma plays in the lives of our marginalized peoples. There are Indigenous communities that have their own police services where all, or the majority, of their members are Indigenous. Many of these good police officers have struggled with the fact that some community members could still fear them. The same holds true for Black police officers working in predominantly Black neighbourhoods. But much of what influences our current functioning is our past, including the lived experiences of our parents. The uniform itself is therefore traumatic stimuli to some people who, because of hypervigilance and hypersensitivity from prior trauma, cannot see the person behind the uniform. There are likewise many Indigenous schools operated locally with the majority of staff being Indigenous who bear the traumatic weight of racism twice: once by the effects of colonialism and residential schools on them personally, and a second time as staff, by discovering that some families in their own communities now see them as part of the “system”. In other words, schools are still traumatic stimuli to parents and grandparents who were forced into residential schools themselves and because of multigenerational transmission of symptoms, their children and grandchildren bear that weight also. This same process of traumatization is profoundly evident in the Black Canadian community and clearly manifested in America as well. For some immigrant families, they have brought their own stories of trauma where men and women in uniform in their former countries have committed atrocities. As alluded to earlier, only the “right cops” can work with students and schools and have success: and they must be trauma-informed.

What are SRO’s Doing in Canadian Schools?

In schools where there is not ongoing review and collaboration between school leaders and police, the SRO program can vary from student engagement and relationship building on one end of the continuum to enforcement on the other. Some school districts prefer to have their SRO’s spend the majority of their time doing classroom presentations. At its highest level, SRO’s should be developing meaningful relationships with all students with a special emphasis on those who are marginalized or racialized for the purpose of creating a genuine experience. Police who understand the effects of trauma including systemic racism are best positioned to have a positive impact on student well-being. Police who see “ensuring safe and caring schools” as a broader social dynamic understand they are becoming part of the school family which generalizes into them becoming part of the overall community family. Although there should be flexibility in the roles SRO’s can play in the school, there should be a primary emphasis on creating an open dynamic between students, staff, parents (caregivers), school administration and the SRO where the physical, emotional, cultural and racial safety of all are paramount.

Some SRO practices in Canadian schools are not because the police officer wants it that way but because school administrators do. This means that some SRO’s sought out the specialized role of working in schools because of a desire to work with and support students. The difficulty has been that occasionally there have been school administrators who wanted them primarily to “police” their school in the traditional sense of law enforcement. In this sense some police have been set up by the school to play a role the program never intended. This can leave police being directed by the school to engage is practices that may be consistent with the administrator’s racial bias rather than the SRO’s. This is the complexity of systemic racism.

Where the role of the SRO is a focused priority for police and school, evidence suggests positive outcomes in multiple areas benefiting students. In the 2019 study of a large Canadian school district where white students made up approximately 20% of the student population, the authors noted that:

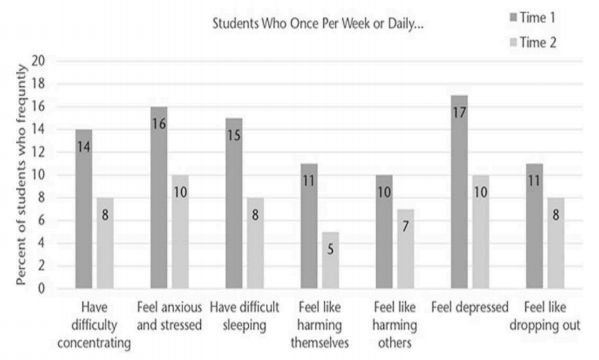

Five months after becoming a student at a high school with a full-time SRO, the students who responded to our survey were significantly more able to concentrate, in better mental health (i.e., reported less anxiety, stress, and feeling depressed), less likely to report difficulties sleeping, and less likely to think about harming themselves or others. Given the data showing that these students who feel safer are also less likely to skip class, miss school, and be thinking of dropping out, we also expect that students who feel safer are also more able to take advantage of the learning opportunities offered in the school.

“Police in Schools: An Evidenced-Based Look at the Use of School Resource Officers” Linda Duxbury & Craig Bennell

The key point here is that a thoughtfully constructed SRO program established in collaboration between the district and the police leaders can and does yield very positive outcomes. In the face of the growing anti-police sentiment, such a program is a positive way to strengthen trauma-informed practice to truly be an ally to the racialized community to bring about positive change.

Hearing the Concerns of Parents, Students and Others

The movement to have historical trauma and modern-day systemic racism addressed is a positive societal outcome of the mounting stresses of a worldwide pandemic combined with the realities of how the scales of justice and mercy are not blind nor equal for all. As such the call has come from some advocacy groups to remove police from schools. Because of heightened anxiety some leaders of school or police systems run the risk of making decisions about police in schools based solely on avoiding the difficult process of thoughtful review. In other words, if the request to remove police from school is made to a school board then some may comply even when their SRO program is what is keeping one school culturally and racially safe. When one party “gives in to the demands” of another, not because it was right, but because it momentarily avoids a conflict, there will be resentments and no real change.

Abbotsford: A Case Study in Developing a Safe and Culturally Committed Environment

As the gang conflict expanded across the Lower Mainland, it would have been easy for the Abbotsford Police Department to restrict their intervention to enforcement of the young men in the city, many of whom were of South-Asian descent. The issue of race surfaced numeroustimes as the community struggled to address the issue. Rather that retreat from these concerns, the SRO program became a critical part of the multi-pronged approach now used in the city. It was certainly a delicate matter, but the police chief and school leaders created space for the community to tackle the issues openly. What was abundantly clear was the need to listen (and listen carefully) to the concerns presented by the community. This required courage. Soon thereafter, community leaders began to welcome the police chief and school district superintendent to speak at community temples to the parents and youth about the important and joint role we play in raising healthy, safe and productive children. These meetings spawned a series of changes intended to prevent the next generation of students from ever entering gang life. This strategy involves co-sponsored programs between school district, SRO and community members involving awareness, education, recreation, service, mentorship and enforcement. This is what is possible when you listen with a good heart and commit to taking action based on what you hear.

Where indicated, proper reviews must be conducted. Otherwise, those who lost the first battle will lie in wait for the next to occur and then they will lull the system back to its original state. Without openness and honesty, all human systems tend towards homeostasis which is the lowest resting state for the majority. If leaders feel forced, the system will eventually return to the same state. This is why data-driven and collective assessments of SRO programs is the only process that can result in legitimate change because all will see the realities of whether the program is good, great, in need of modification or beyond repair in its current state.

Considerations for SRO and School District Assessments

As we expand our consultations, there will be a follow-up set of Guidelines for Assessing SRO Programs in Canadian Schools that will include:

- Assessing the differing roles of SRO’s in Canadian schools (district to district).

- Assessing the differing roles school administrators feel SRO’s should have even within the same school district.

- Prioritizing the “Relationship Building – Enforcement Continuum”. This include identifying important ‘stakeholder groups within the school and community as well as pathways for regular and ongoing communication.

- Data-Driven Assessments of SRO Interventions.

- Characteristics of a Trauma-Informed and Culturally Committed SRO.

- Characteristics of a Trauma-Informed and Culturally Committed School Leadership Team.

- Characteristics of a Trauma-Informed and Culturally Committed School District and School Board Leadership team.

- Prejudice and Racism as a Dichotomy.

- Open Systems: Sustaining Community Engagement.

The primary purpose for releasing this document is to provide school, police and community leaders with a systems perspective to ensure lasting change occurs during this pivotal time in our nation’s history. Understanding how trauma influences human systems was the impetus for our public call to proper data-driven assessments and proper data-driven interventions. Systemic change occurs when all are humanized! Black, Indigenous and other races and cultures have experienced the pains of individual and systemic racism over generations. Most Canadian school districts and police services are primarily led by white professionals who have dedicated their careers to serving but have not experienced racism themselves. So, interacting with people from the “Black Community” or “Indigenous Community” is not the same as hearing and comprehending what is being said about real lived experiences. Prejudices occur because we have not thoughtfully considered the “other” as fellow human beings but have considered them as only different from ourselves. Rather than withdrawing from the SRO programs, school and police leaders should ask themselves about the kind of community they wish to create. If we wish to live the ideas of embracing diversity, equity and inclusion we should then courageously engage the community, particularly the racialized community about how the SRO program can reflect those values. We have an opportunity to do what others could not fully do before us: prove that multiculturalism can work.