Second Wave: Matching Resources to Risk During Remote Learning

File: PDF Version Second Wave: Matching Resources to Risk During Remote Learning

Author

J. Kevin Cameron, Executive Director NACTATR

Introduction

As noted in the first two School-Related COVID-19 Guidelines released by the North American Centre for Threat Assessment and Trauma Response (NACTATR), the most significant risk enhancer for some of our students was going to be the effects of quarantine. In particular we were concerned with the impaired “Closeness-Distance Cycle”. We have inserted the link from the original article here because it is the most dominant variable contributing to escalations in violence, suicide and child abuse in general.

(See Closeness/Distance Cycle: http://nactatr.com/news/files/Closeness-Distance.pdf).

These current Guidelines are based on the above article: if you are not familiar with it please read it now.

Prior to the start of this academic year, we anticipated that some of our highest risk students from high risk family circumstances would be so relieved to reengage with school staff and their peers, that their conduct for the first two months of return to school would be above expectations. We also noted that after that period we would begin to see their behaviours escalate by early November as the more secure and consistent reconnection with staff would eventually “free them up” to manifest the burdens they were bearing. A primary concern for the second wave of COVID-19 and re-entering quarantine is that our students (and staff) who were subjected to abuse in all its’ forms during the first quarantine will not manage as well the second time around. In essence, the first wave was new to us all and some figured out how to accommodate it but with the second wave, those we are concerned about know how difficult it was and feel they cannot survive a lengthy quarantine again. The best intervention that schools can provide is to be thoughtful and creative about how to stay connected to our students and their families as much as possible.

Some students had already gone truant during the first wave and losing them a second time will be much harder to recover. Unreasonable expectations have burdened many educators to maintain pre-pandemic educational standards. The real focus should be first, maintain relationship connection and second, educate as possible our Students of Concern (SOC). The phrase “matching resources to risk” refers to a standard addressed in the Guidelines from March 2020 where recommendations for identifying who the higher risk students may be, and who was the best person to be the primary contact, were presented. As connection is the priority with our high-risk students, all staff should be considered as a potential “best fit”. For instance, in Case “A the former teacher may be better suited because of a prior relationship with the family while in Case “B” the educational assistant may be the best stabilizer for the student.

Purpose

The primary purpose of the Second Wave Guidelines is to assist school administration and their teams with preliminary considerations to match students’ risk to the best resources available, during the “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic. We observed that in the initial phase of the pandemic, there were fewer resources for students and therefore the need to support them socially, emotionally, and educationally required a strategic collaborative strategy. The importance of collaboration becomes equally if not more important during the second wave. The prolonged impact of the pandemic has intensified dynamics already embedded from the first wave. Many of our students of concern (SOC) are already struggling emotionally-behaviorally, and some will be at further risk because of intensified family dynamics during a second quarantine period. As teachers and other school staff work to stay connected with students, it is essential to apply a trauma-informed approach to guide administrative decisions.

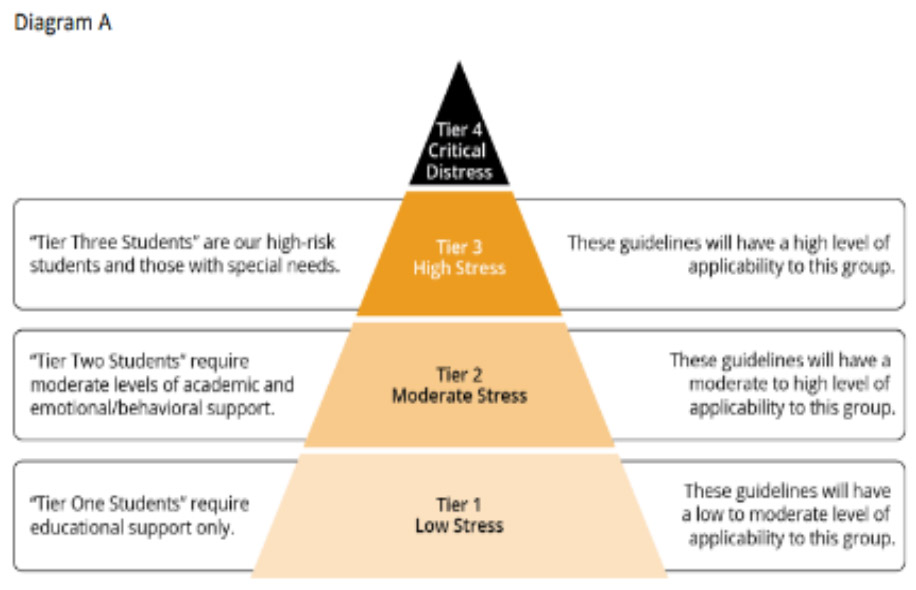

The guidelines will inform, educate, and direct professionals in collaborative decision making related to: frequency, intensity, nature of student to staff contact, strategically matching staff to students and providing consistent guidelines for student engagement as educators and support staff are now “virtually” entering into the family’s home for the second time. These virtual visits may shed light on situations that may require external support for students or the family. A distinction is made between “Tier One Students” who require educational support only, “Tier Two Students” who require moderate levels of academic and emotional/behavioral support, and “Tier Three Students” who are our high-risk students and those with special needs. Tier Four is an acute designation for students in immediate crisis where child protective services, police, or psychiatry are intervening. These guidelines are primarily focused on Tier Two and Tier Three students (See Diagram A) and matching resources to their risk. However, the recommendations for students of concern may become relevant for some Tier One students as the weeks go on and individual family stresses increase.

Collaborative “triaging” will require two very important considerations in managing “second wave” effectively. School based trauma informed teams understand that the compounding effect of a second wave and the holiday break can potentially shift the family dynamics differently. Meaning, a students’ function during the initial wave of the pandemic may possibly look different in the second wave. For example, a student and their parents/caregivers may have experienced unforeseen loss, grief or trauma not known to the schools’ staff. Secondly, the overall functioning of the organizations’ staff may shift in the second wave of the pandemic. For example, a staff that had the ability to weather the storm in the first wave are feeling emotionally depleted and not as confident as they enter the second wave. The shift in teachers’ confidence during COVID was illustrated in a 2020 study by the New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. When asked “how confident are you that you are adequately prepared to address the stress and trauma of students?”, over half of the teachers in this study reported that they were somewhat or not at all prepared to adequately support students.

This resource is focused on a trauma-informed educational response for the identification of student-staff-family capacity for learning and to formalize reasonable student support. Teachers and school staff are providing supportive education, not family crisis intervention. Therefore, they will need to understand the impact this crisis is having or will have as time goes on. These guidelines will assist traversing the most unique challenge of our collective lifetimes: a world-wide pandemic.

Loss, Grief and Trauma are Not the Same: DEFINING LOSS, GRIEF, AND TRAUMA

No two schools are the same. Leadership style (past and present), overall school staff dynamics, parent-school dynamics, demographics and history of trauma prior to the pandemic will all play a major role in supporting staff and students during the second wave. As such, the Crisis and Trauma Response Continuum will vary from school to school and community to community. Loss of employment, restrictions on the ability to maintain connection with loved ones and the stresses of an impaired “Closeness-Distance Cycle” will add to the impact on some students and their families. Understanding what happened in students’ lives from the time between schools closing and reopening will be critical to determine how school districts/divisions should match “resources to risk”. While traumatization will vary in frequency and intensity throughout the Continent, the impact of grief and loss will be more pervasive. However, loss, grief, and trauma are not the same and not every sadness is about the death of a loved one.

Non-Death Related Loss is defined as emotional distress following the realization that an event, experience, or opportunity will not happen or not happen in the way it had been anticipated. This includes human relationships and connections not including death. In the school context, this could be missing a sports scholarship, modified graduation, not participating in other school organized extracurricular activities or not being able to say goodbye in person to a favorite teacher who is retiring at the end of the year. It is certainly about the physical and emotional connection with peers and an overall loss of a “natural” life course that others had before them who were not subject to a worldwide pandemic.

Emotionally Detached or Complicated Death-Related Loss is defined as a familial loss or close-connection loss that is not impacting a family member or friend of the deceased in ways others assumed it would. The reaction of the family member or friend is viewed as an unnatural grief response by others. When the response is not typical of others’ expectations of how loss should be displayed, the result is increased anxiety for all as they try to understand the complicated response. This occurs primarily because the beliefs by others about the relationship between the identified “grieving person” and the deceased are assumptions. A common example that can result in emotionally detached/complex loss is that of a younger sibling abused by an older sibling who is now deceased. Perhaps family and friends were unaware of the abuse and, attuned to the weight of grief on the family, the younger sibling (the victim) keeps the secret; yet remains not visibly saddened by the loss. To outsiders observing, this response will appear incongruent, but if they knew the context, it would seem very congruent.

Grief is defined as “the intense emotional distress we have following a death. Bereavement refers to the state or fact of being bereaved or having lost a loved one by death. Mourning refers to the encompassing family, social, and cultural rituals associated, and the individual and psychological processes associated with bereavement. Thus, when you are bereaved, you feel grief, and mourn in special ways.” – NCTSN. Loss, not associated with death, and grief may both elicit the same powerful emotional responses and necessary processes for recovery. It is essential for professionals to understand the distinction among loss, grief and traumatization because all three could be interacting within the walls of the same school or within the emotional experience of the same person. Some schools are in “hotspot” communities where individuals attached to their school community have died because of the virus. This means that some students and staff may be dealing with the weight of grief. Others may have witnessed a family member dying and encoded the experience as traumatic. Thoughtful consideration, caring and compassion will lay an unshakable foundation for how schools support students, staff and their families alike.

Trauma as defined in the “Traumatic Event Systems (TES™) Model” and the “Crisis and Trauma-Response Continuum” denotes that during any traumatic event individuals will experience a range of responses from no impact (they are doing fine) to acute symptom development, chronic symptom development, delayed reaction, complete repression to overt traumatization. Failure to understand this reaction range has resulted in many individuals referring to any form of distress as “trauma”. Even among some professionals, one of the most misused and misunderstood words is trauma. Trauma is stored in the body and the brain at the cellular level. That means that while a human organism may try to psychologically deny the impact of traumatic exposure and encoding, the body may (and often does) manifest symptoms whether we want it to or not. In general, many students and staff will not be traumatized but in some schools, they may. The height of traumatization is when the “human organism is placed in such a state of disequilibrium that they are thinking, feeling and doing things they have never done before” months and years after the threat is no longer present.

Preparing Staff for the Second Wave: Connection, Collaboration, Compassion

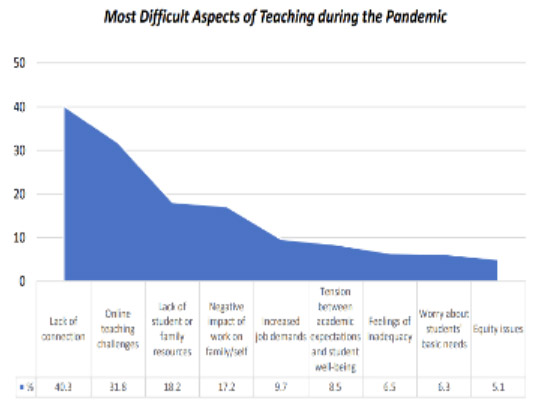

For the last 8 months, educators have supported students with the compassionate professionalism that drew them to the profession. Traversing these times has presented some emerging challenges echoed in many NACTATR conversations as well as the research. Referencing again the New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative (2020) study, educators reported the “lack of connection” and “online” teaching as most challenging. As we have entered the second wave, one can conclude a similar hypothesis as presented in the study. Connection between colleagues, between staff and students, and school to community become essential elements for preparedness.

Some of the essentials in managing a second wave are grounded in the key NACTATR principles presented in the https://nactatr.com/news/files/01GuideRe-Entry.pdf, and support trauma informed decision making that ultimately lowers the collective anxiety of the system. Such as:

1) Make your world small: Rather than focus on the media-intensified macro dynamics in society focus on the micro dynamics you have power to control (self, family, classroom school, community).

(Click for video: https://twitter.com/JKevinCameron/status/1303686884908908549)

2) Reasonable expectations: It is not reasonable to set organizational expectations that suggest that our school will be “COVID-free” or that our pre-COVID attendance will remain the same during the second wave. Conversely, stating that is possible that we will have cases and here is our planned response to it, lowers overall school anxiety.

3) Two staff members can absorb more anxiety than one can on their own: Trauma informed staff understand that connection goes beyond “proximity”. Just because we are employed and work in the same school does not mean we have equitable connections with each other. Like our students, ensure that every staff member is connected with at least one colleague/co-worker who forms part of their work support system.

a. Creating natural connections that are organized around pedagogical support is also essential. For example, connecting a “tech savvy” teacher with a teacher who struggles with technology is important.

b. Creating a natural connection by subject: Some divisions are reallocating teachers, out of necessity, into subjects they have not taught in years. Dedicating some time to share resources, share tricks of the trade immediately lower teacher anxiety. (Note: Use your substitute teachers, retired staff etc.)

4) Two schools can absorb more anxiety than one can on their own. Connecting with another school from time to time and comparing notes on their successes and some “surprises” that they have encountered during the first wave may be helpful in maneuvering the second wave. A two school Zoom call can help to normalize the many experiences professionals are having and increase creativity and hopefulness for moving forward.

5) Everyone is entitled to have a good melt down from time to time. 10 different staff members will all have 10 different thresholds on bearing the weight of the pandemic. Naturally open systems/leaders allow a variety of emotions to enter the system without judgements. A mini-meltdown should be expected every now and then.

6) Debrief and Celebrate: Devoting some time to celebrate pandemic victories publicly among staff helps to attach positive meaning to an otherwise stressful time. The notion that growth can occur during traumatic times lowers individual and collective anxiety. For example, in the Harvard Business Review (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30268956/), over 50% (n=10000) of trauma survivors reported traumatic growth described as: a stronger connections, greater overall purpose, and a deepening of spiritual values. Other examples from the research include: a) more quality time with family and friends b) new connections c) paid more attention to personal health d) found greater meaning in my work.

Matching Resources to Risk: Where do Students go when in Crisis?

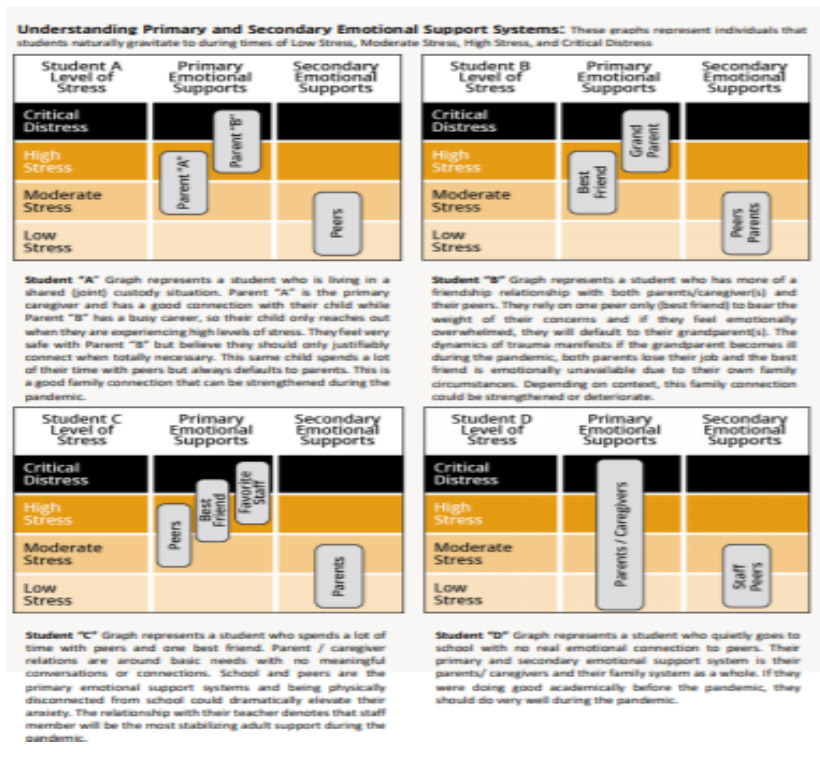

As some schools have been temporarily closed during the second wave with many classes returning to online instruction, the weight of connection for some of our students and families has fallen more uniquely on educators and other school staff as the primary or only point of contact. In the Traumatic Event Systems (TES™) Model, a distinction is made between a student’s “primary emotional support system” and “secondary emotional support system”.

(Page 9, http://nactatr.com/files/2020NACTATR-RisingChallenge.pdf) The primary emotional support system is the individual or individuals (often parents or family members) that a student is naturally drawn to when in distress. For them, prior connection and relationship experience denote that if their anxiety or fear begins to escalate, or spike towards their fight-flight-freeze threshold, they will default to that person(s) for support. In some families, children and youth do not want to “hang around” with their parents/caregivers because their peers “seem” more important. The most reliable way to assess someone’s primary emotional support system does not depend on who they spend their time with when things are going well; but who they gravitate to, for support, when things are not going well. As such, the secondary emotional support system is who the student enjoys spending time with when their anxiety is lower. The good news is, for most students their home life is stable. Therefore, balancing the learning needs of students with their emotional well-being is a dynamic that most educators were experienced at prior to the pandemic. The current circumstance has now shifted that support from the confines of the school environment to the home environment. The most reliable way to assess someone’s primary emotional support system does not depend on who they spend their time with when things are going well; but who they gravitate to for support when things are not going well. The challenge, that is contextually intensified by the second wave, is that for some students, key staff members are their primary emotional support system. These students may feel abandonment and fear due to the physical loss of school staff and student connection. This will be intensified if they live in an emotionally disconnected home or if they are at risk of more tangible forms of abuse. Therefore, “text or talk” and “online or virtual support” is essential to assist the student as a whole person, impacted by the effects of a world-wide pandemic. For some of these students, the sound of the right voice, the right words and regular connection can provide them with stability and hope as they maneuver through this unique shared experience. For some of these students the continuation of their studies, from a distance, will be their ongoing drive to succeed. For others it is a distraction from the mundane, and for others the excuse for contact with outside adults they hope can be a lifeline if they need it. No matter what the family circumstance may be, there is also a temporary dynamic that must be understood by all educators and school staff who are reaching out to students and their families. To many parents and caregivers, “the school” is a powerful hierarchical entity in which they are not always sure where they fit. For some parents there is significant anxiety generated when dealing with the school even at the best of times. In many cases, the pandemic has shifted that dynamic because now the school is, in essence, entering their homes. Especially when connecting virtually, staff are entering a space where most had never been in before: the family home. Although these are unprecedented times in our world, the power of human connection remains the single most important variable. Unified in the same goal of supporting students, our contact with them and one another will continue to move us forward.

Practical Applications: Matching Resources to Risk.

Each school varies as to how many “identified students” with special needs or vulnerabilities they have. How many students have complex emotional or behavioral difficulties and how many students are staff intuitively worried about? In particular, due to suspected concerns of a trauma history such as: abuse, chaotic family situations, substance abuse, unemployment or financial stresses, etc. In some schools, staff to student matching would be according to already established educational relationships. However, with students of concern, where school staff may also be their primary emotional support system, thoughtful and strategic matching will be essential. This also includes high-achieving students where their self-concept and self-worth is obtained through their academic success. If school staff is their primary emotional support system their risk for depression, anxiety and other clinical conditions may be exacerbated. A Standard in the fields of Violence Threat Risk Assessment (VTRA™) and Crisis/Trauma Response (TES™) is: “The higher the anxiety, the greater the symptom development”. Therefore, to lower the anxiety of students of concern and their families, there should be consideration into who is the best person under the current circumstance to be assigned as the primary school contact. In higher risk or more complex cases, there should be consideration for having a secondary contact.

Quick Reference: Matching Resources

1. The better the data the better the assessment, the better the assessment the better the intervention. As educators collaborate, recalibrate and accommodate to the second wave; one of the key questions to ask is: What did we learn about student A, during the first wave of quarantine, their re-entry into school, and anticipated challenges and strengths for the second wave?

Resource: Family Dynamics During a Pandemic. (http://nactatr.com/risingchallenge.html#audio)

2. Planning for Quarantine/Remote Learning Interview. Ask the student:

- How do you feel you did with remote/distance learning the first time we went into quarantine?

- Are there aspects of going back into quarantine you are looking forward to?

- Are there aspects of going back to remote/distance learning you are looking forward to?

- What are you concerned about the most going back into quarantine?

- What are you concerned about the most going back to remote/distance learning?

- How will I know if you are struggling (emotionally, educationally, etc.)?

- Counsel me and tell me how I should help you if I sense you are struggling?

- *Being mindful that the “quarantine” questions are about the family dynamics (learning environment) and the “remote/distance” learning questions are about education.

3. Who do you want to have as my back up? This a question that the appropriate staff member should ask students whose primary support system is believed to be school personnel. The designated school lead for that student should ask directly “Who do you want to have as my back up?”. This question is intended to say, if I can’t respond to you as soon as I would like who on staff would you like to be my backup. The answer will give insight into who that student feels would be the best fit for them. Do not be surprised if the student identifies a staff member they do not know personally or know that well. Sometimes a student watches how a particular staff member interacts with other students and just feels drawn to their personality. Naturally open systems are open to connecting students with: former retired teachers, assistants, substitute teachers, custodians, administrative support.

(See page 12, http://nactatr.com/files/2020NACTATR-RisingChallenge.pdf)

4. Timing is Everything. Ask students when the best time is to connect one on one and ask if they have a preferred way of saying “now is not a good time”. Family dynamics and circumstance can encumber the remote relationship as tensions in the home may prevent making a good connection at this time. Students may say the best time for a one on one conversation may be early in the morning or right after lunch etc. Or they may say “if you call and you can tell my step-dad is there then know I will only talk with you briefly”.

5. Mode of communication and connection? Some students and even adults may be more truthful and/or emotionally open depending on the communication method. We have found that some high-risk youth will not open up on a Zoom-type platform where they are seeing the adult in person. Yet, they will be open on a telephone call if the timing is right (they are alone or in a private space). Others will be more open texting while some do not care about the mode of communication, they just care about comfort level with the adult.

6. Most Schools have VTRA™ Protocols so “Tell Now if You are Concerned”. Most School administrators and counsellors are trained in Violence Threat Risk Assessment (VTRA™) as are your community partners in police services, social services, mental health, probation and others. If you already know or have reasonable grounds to believe that a student of concern is going into a home situation that may place them at risk tell your school leaders. They have the training and formal protocol connections to investigate and intervene.

J. Kevin Cameron, Executive Director

North American Center for Threat Assessment and Trauma Response